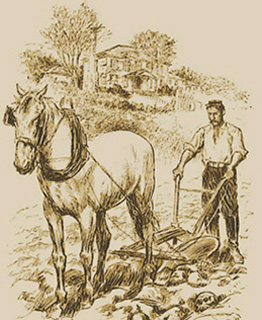

The Farmer

By the time John Dickinson and his brother inherited his father's farm (1760) then called Poplar Hall on St. Jones Neck, south of Dover, Delaware, farming this property had become almost a sinecure. The Dickinsons could afford long absences. John Dickinson had grown up on the farm and now was a Philadelphia lawyer focused on colonial politics, but he called himself a farmer when writing his most famous Letters From a Farmer in Pennsylvania in 1767. Unlike smaller homesteads, Poplar Hall was a plantation organized to produce income from numerous tenant farmers who worked their allotted sections to meet production quotas using Dickinson slaves (freed in 1786) for labor.

Towards the end of the 18th century, John Dickinson owned more land than anyone in Kent County. His landholdings began with his inheritance; but he aggressively purchased more land in Delaware and Pennsylvania . His marriage to Mary Norris of Philadelphia afforded even more property. His real estate included land in Kent and New Castle Counties, as well as holdings in Pennsylvania, but he called his father's Poplar Hall "Homeplace" and a "prospect of plenty".

Towards the end of the 18th century, John Dickinson owned more land than anyone in Kent County. His landholdings began with his inheritance; but he aggressively purchased more land in Delaware and Pennsylvania . His marriage to Mary Norris of Philadelphia afforded even more property. His real estate included land in Kent and New Castle Counties, as well as holdings in Pennsylvania, but he called his father's Poplar Hall "Homeplace" and a "prospect of plenty".

When he died in 1808, Dickinson owned over 5,000 acres in St. Jones Neck in Kent County. The plantation was carefully supervised with significant intervention on his part. With soils unsuitable for tobacco, the plantation grew wheat, rye, barley, and orchard fruits.

The tenant farmers, whose backgrounds varied, oversaw the upkeep and production of their portion of Dickinson land. They reported to Dickinson on a regular basis. If they could not meet their lease agreements, employment was at risk. The successful tenants followed specific husbandry protocols outlined in their lease agreements to produce market quality output. Some were hired for purposes other than growing crops. William White for example, tenanted "Homeplace" and produced candles, soap, lard, wool, flax, beef and pork. While tenant farmers were typically viewed as landless, William White owned land in his own right. Other tenant farmers included free blacks and poor whites who typically owned little, never acquiring land.

Land on St. Jones Neck was typical to coastal Delaware. It consisted of marsh, wooded, and cleared land. Natural features of the land were utilized wherever possible. The cleared land grew grain crops because tobacco had ceased to be a profitable Delaware crop in the early 18th century. Orchards and woodlands provided sources of fuel for heating, cooking, laundry fires, as well as construction for habitation and many other tasks. Finding wood for fuel became a problem in the latter 1700s when more land came under tillage and trees were becoming scarce to the landscape. Seeing the need to reform, John Dickinson required all building repairs and fencing to be completed with dead tree material. Wood from live trees could only be used for special projects.

John's attempts to improve the landscape was part of a larger effort by many at a full scale agriculture reform. John Spurrier, who may have been a tenant of Dickinson's at one time, wrote a book on reform methods. Gentleman farmers, like Dickinson, debated the reform issues and implemented many programs. This did not alleviate the problem that had become too intense for a quick reform by the end of the 1700s.

Styles of fencing and ditching efforts to better utilize marsh land were two methods of agricultural reform that Dickinson carried out. However, John died in 1808, just two years after he rebuilt his boyhood home that was damaged by fire. Dickinson's "prospect of plenty" was in need of careful management. Sally Dickinson, John's daughter, assumed the responsibility of running the Jones Neck property until her death in 1856.